How our terminology restricts our understanding.

(From AFTERSUN, 2022, Writer-Director Charlotte Wells, Cinematographer Gregory Oke.)

What do we mean by the term ‘negative space on a movie screen? An expanse of emptiness, of lack of action, an area beside or outside the place in the frame to which our eyes are drawn, a section of the screen devoid of image, of people or objects, a blankness, that (seemingly) lacks tension — aren’t these some aspects of what we might understand by the term negative space?

It sounds so pejorative. After all, it’s a negative, a minus, a less than anything. You’d think there’d be an opposite term, a positive space. There isn’t, or if there is I’ve missed it, but it’s there by implication. It’s as though no space in the frame matters if something isn’t filling it — and that something needs to be a person or an object, an event, or some presence or other at the very least.

How might we usefully reconceive this phenomenon?

Firstly, how might ‘negative’ space prove to be functional space? How might it interact with other areas of the frame? Have an effect on them?

Asw ith the frame-within-the-frame, an area of “negative”, apparently inactive space can give rise to a new aspect ratio. The newly proportioned segment on the remainder of the screen that contains something — the “positive” space, as it were — is afforded additional emphasis. Such an approach is effective in 2.35:1 especially although can work in other formats of course, the greater the blank area the greater the effect on the constricted remaining section.

This goes for an image too. In Charlotte Regan’s 2022 Scrapper, there’s a shot in which a blank, off-white (as I recall) monochrome wall takes up the entire 2.35:1 frame. Gradually, to the bottom right of the screen and not in close-up but decidedly tiny in the picture, the hands of the young female protagonist rise into shot — all that can be seen in front of the blank wall. The effect? It’s mesmerizing. The moment, the simple, unremarkable action is rendered somehow significant. We watch intently what we might otherwise barely notice.

Think also of where the filmmaker might situate blankness. To the left of the frame, to the right, centered or around the third so as to divide the screen into three sections, three frames. These variations serve to surprise, stimulate, and refresh the visual interest of the viewer, whose shifting gaze travels now around one area, now another. Emptiness and presence dance around the screen, occupying alternating domains. The frame becomes dynamic, a universe for the viewer’s visual journey in its simplest aspect.

There’s a related insight we need to consider. In what part of the frame do we find the space? Top, bottom, left, right — don’t these sections have inherent qualities? Stable/Less stable. Home/Away. Past/Future. Heaven/Hell. Death/Life. Safety/Danger. Setting out/Returning. Where there’s space, where there’s action, what the screen direction of any movement, and what (usually subliminal) meaning is afforded by the relative positioning.

And how might this agility, spatial, lateral, vertical, relate to depth? After all, empty space may be found in a mid- or background of a shot, but also in foreground — perhaps a surface devoid of detail, perhaps one out of focus so that any detail is indiscernible. Again, the viewer’s visual engagement is enhanced, focal planes of something and nothing interacting.

When it comes to the technique of short-siding, blank (“negative”) space can be notably effective. Two characters converse. In one shot, one, in profile, looks to camera right, the other, in the intercut shot to camera left. In a widescreen format, the first might be seen on frame left, the second frame right. Say in both shots there’s corresponding “negative” space across the rest of the screen. That space in each shot, will hold a tension. Each is weighted. The dialogue, the characters’ looks give each space a charge. They may be ‘negative’ but they are active.

Such an approach might indicate a physical distance between the characters also. But when they are not in the same place, on the phone to each other, the effect can emphasize their geographical separation too.

Say, to the contrary, that each character is placed close to the side of the frame to which they are looking, the device known as short-siding. In this case, the space behind each will be devoid of charge — unless we anticipate the appearance of another character or element, so that the shot becomes suspenseful. (When will x appear? we wonder.) When there’s no such expectation, the charge of each shot will rest in that narrow sliver of the screen between the characters and the frames’ edges.

If we are not expecting some new entity and one suddenly appears, then we are surprised, startled. The empty space, abruptly active, thus prompts a jump scare. The emptiness was a misdirection.

Such dynamics of charge or no charge might apply to any lateral composition, not only one utilized in cutting between profile singles. (And to a vertical axis, particularly with a 1.33:1 aspect ratio.) If we expect a “negative” space to be filled we may be either held in suspense — in which case it is rendered potent space — or if we know the new element to be merely innocuous we may become bored because such anticipatory framing goes on for too long.

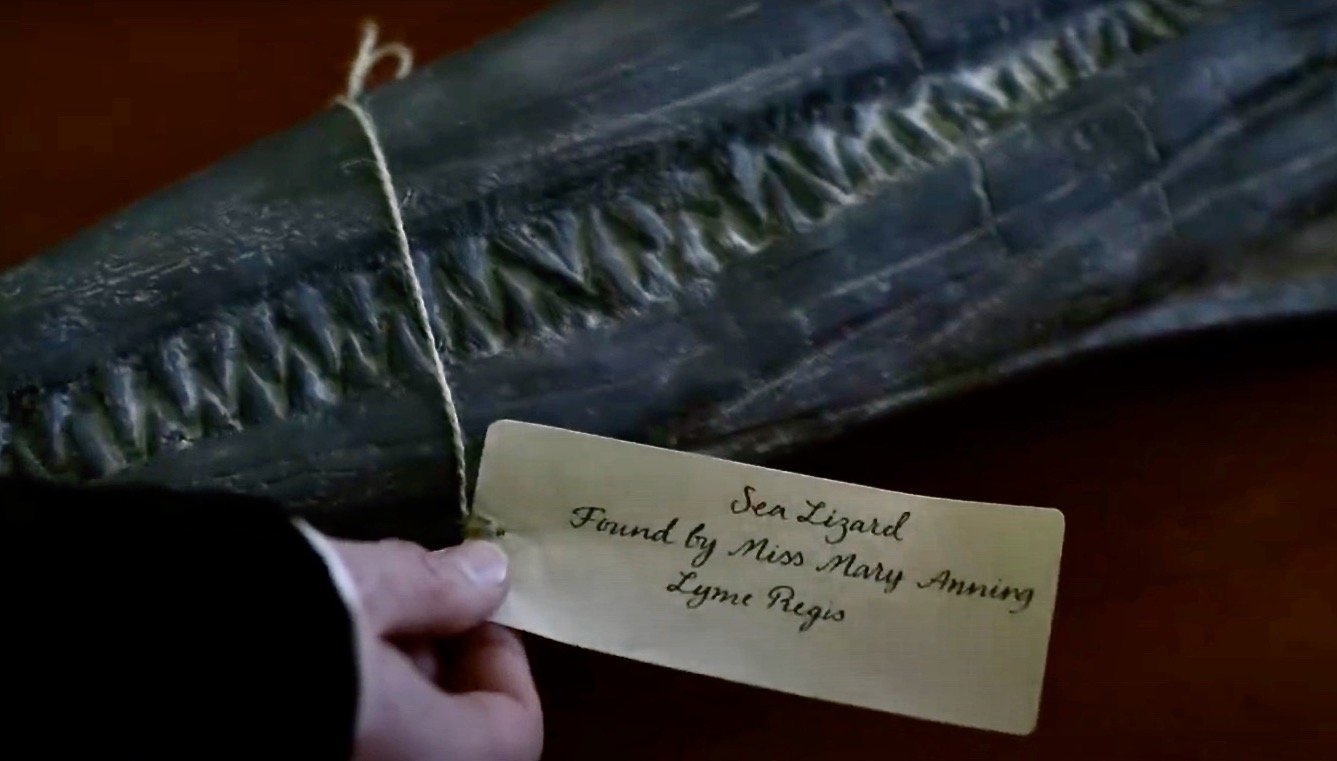

We might also consider how a shot introducing a scene might consist almost entirely of absence. Perhaps there are elements bordering the frame to one side of the other. This can be seen in the screen capture above from Charlotte Wells’ remarkable debut feature Aftersun, in which we begin, as the camera slowly pans right, to a see Calum’s arms in the mirror to frame right as he practices his tai chi movements. As the camera movement continues, his arms come into the foreground of the shot — and then we understand what we are seeing.

In other words, the initial emptiness over which the camera passes is instrumental in the process of revealing the meaning of the shot.

A second consideration might be the value of emptiness per se in the frame.I’ve written about this before in Cinema’s Mesmerism of Absence but it’s worth repeating — and in relation to the points above — that absence, that space itself, room in the frame, passive space we might call it, can lay claim to the screen. Like the passive character, this might be heresy to the practitioner or teacher of aesthetic and dramatic plenitude but given that by orders of almost infinite magnitude emptiness would seem to be the larger component of the cosmos, why shouldn’t it be granted territory within the frame of a movie now and then? And why, what’s more, shouldn’t we savor the presence of absence?

Like stillness, like silence, like nothing happening, and the resonance such a hiatus can foster, “negative” space is a fundamental, essential cinematic resource. Without seeing what is not there, we cannot truly see what is.

Besides… without emptiness there can be no wonder.

Peter Markham

May 2024