Subconscious Messaging in Cinema

Filmmakers and the Psyche of the Moment (From Medium February 2021)

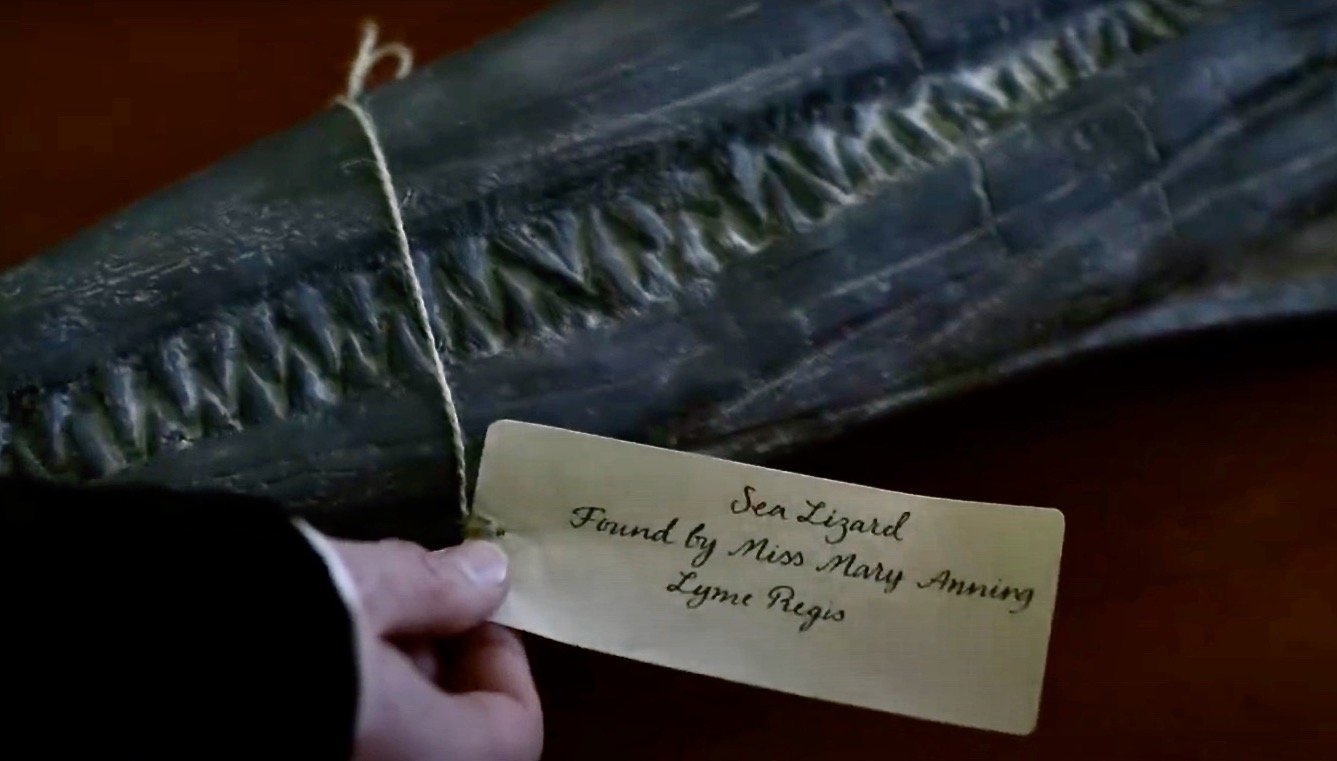

From Ammonite, Cinematography Stéphane Fontaine

How aware is the filmmaker of the messages their film might be communicating? Not the intentional but the unintentional ones. How aware should they be? How aware can they be? And how much is an audience conscious of the messages they receive? Do the unintentional missives of the filmmaker follow pathways into the unsuspecting minds of their audiences more insidioius than any intentional messaging? Certainly, a director like Hitchcock could intentionally sway an audience one way or another by a simple sound in the background barely noticeable but subliminally efficient in evoking, say, a wish for a character to travel (a train whistle), or to lay the foundation for a suspicion of guilt (a police siren). Filmmakers use intentional subliminal messaging all the time — or they do if they’re proficient. The audience doesn’t realize how it’s being played, and even if it did, probably wouldn’t complain. Cinema, its practitioners know, delves deep into the psyche, into subterranean depths we all of us share. Do they realize though, that it works the other way too — that if a film can exert influences over its audience, the zeitgeist, the undercurrents of contemporary culture and its leanings can also exert a power over its makers — whether they go along consciously with those inclinations or they don’t? Once those proclivities have become embedded in a story, the story exerts agency over filmmakers unaware of the meaning they then reinforce.

It was Abba Kiarostami who said that a film would mean nothing if it didn’t tap into the memories of its audience, whose members recognize the emotions it evokes and recreates them within themselves. Those emotions may echo the filmmaker’s own as well as having been brought to fruition by the story, the characters, the situation. If the director and their collaborators know what they’re doing, they will have allowed those reservoirs of feeling within themselves to inform their movie. But there are times, surely, when those feelings are too deep, too shared, too universal, to be recognized, even by the creative team itself.

It’s hard enough to grasp the contours of one’s own psyche, but to understand how the psyche of a nation might impact one’s work at any given time, seems to me far more challenging. There’s the conscious recognition of contemporary events, contemporary conflicts, and how these can fuel a story and its drama, but that understanding is limited to known thoughts and feelings about the frictions of the day. Looking back at a period in history can yield insights the contemporary observer has missed. Events, issues, moods, fears and desires may often be the symptoms of deeper instabilities, roilings we cannot comprehend until we see them through the perspective of hindsight.

In 2016, the UK, by means of a plebiscite corrupted by misinformation, voted by a small majority to leave the EU. The visceral instincts were obvious: hostility to immigrants, to people of color, a hankering for some golden age that never existed, a craving for lost imperial power coupled with an island mentality came together to bring out the worst in people. I suspect that few filmmakers supported the move to turn the nation’s back on the European project. Indeed, I can’t recall any notable director or screenwriter hopping onto the xenophobic wagon. One would imagine then, a dearth of Brexit messaging in movies produced during this time.

Not so.

The Darkest Hour presents a Churchill hagiography. A complex man battling with depression, also a racist, a snob, responsible disastrous Dardanelles campaign of the First World War and the Bengal famine, is portrayed as a rollicking populist. Traveling on the tube, which he never did, hobnobbing with passengers of color, which he never did, paradigm of the plucky Brit, Darkest Hour’s Winston comes across as an epitome of the Brexit mentality. Europe was going over to the Nazis — parallel to a controlling, predatory EU, led by Germany as proclaimed by the Tories and the Brexiteers. Darkest Hourwas the perfect vehicle to match their manifesto, and yet few seemed to notice. Performances were praised, direction lauded but the message of the film..? No comment. It dived in too deep to be discerned.

Dunkirk delivers similar plucky Brits, extricating themselves from a dastardly Europe. How the lump in the throat swells when the cottages on the cliffs of England are finally glimpsed, and how the demons of patriotism arouse us! Is Christopher Nolan a Brexiteer? I have no idea. The interweaving of the broad canvas he conjures with the intimate dramas he brings to life hold me and I marvel. But seeing those cottages, those cliffs, and knowing the Brits in their little boats have outwitted the German war machine brings home what’s going on. “Let’s get Brexit done!” Old Etonian Boris Johnson would chunter. He needn’t have bothered. Dunkirk already had.

If those two films don’t offer character assassinations of Europe sufficient, 1917 steps in to fill the gap. Lumbering as the tanks of the day, the movie piles on the contempt for “Johnny Foreigner”. A German pilot, rescued, turns, of course, on his rescuer as against all the odds a single Tommy journeys through an improbable topography, nothing like its historical counterpart, to alert his fellow Brits of some cunning scheme by The Hun, thus managing to get the message through in time to condemn the plan to failure. Germany vanquished again, the Brits in their trenches — ever stoic in their chthonic substrata — prevailing.

The Anglo-catabasis continues with The Dig — England’s treasures excavated deep in the earth when a stubborn archaeologist of modest birth unites with a toff landowner to begin the excavation of the Sutton Hoo treasures. As with Churchill down in the London underground (catabasis again), upper class and low join together to get things done. Former glories are rediscovered, the inheritance of the soil, the safety of the past, history salvation for the present. An Australian director, yes, but the English collective psyche holds sway all the same. Ammonite digs even further, reveling in Mary Anning’s discovery of fossils emerged from the mud. What more perfect symbol for the tired delusions of perfidious Albion than a fossilized ichthyosaur, once lord of the ocean but now reduced to a lump of rock in a glass display case? England as relic. Says it all.

The movie version of Downton Abbey shores up the Brexit edifice, with its upstairs/downstairs bubble, so at odds with the vision of European director Michael Haneke, whose masterly White Ribbon by contrast eviscerates the class system of a rural community early in the last century. Perhaps TV’s The Crown will spawn a movie version before too long, we English reminded of our place — both on the class ladder and in our “splendid isolation” from those continental neighbors across the Channel.

A counter-current? How about Steve McQueen’s visionary Small Axe films? This is England, The Clash sang, and McQueen now reveals, with rather more penetrating vision. Stripped of sentimentality, unflinching in the face of unremitting assault on London’s black English by the Metropolitan Police, righteous in McQueen’s anger but leavened by his warm humanity, these gems glow with the compelling narrative of a new Britain, one we might have missed had we been relying on Brexit Cinema. The story continues, not subsumed into some fake past but vibrant in the present as it reaches to the future. The final film Education begins and ends with 12-year-old protagonist Kingsley Smith gazing up at the stars in a planetarium. (A promise of anabasis). I’m with Kingsley, I reflect. Cosmos over territory. Possibility over fear. Wonder over nostalgia.

Conscious messaging, surely, on McQueen’s part, and an answer to the doubtlessly unconscious leanings of some of his contemporaries.

Peter Markham February 2021