Never underestimate the genius of Film — or that of its new voices.

Elliott Crosset Hove in GODLAND 2022. Writer-Director Hlynur Pálmason, Cinematography Maria von Hausswolff.

Is there a new generation that really values cinema anymore? That’s the dark thought. Richard Linklater.

Born in the final couple of decades of the 1800s, virtuoso of the 1900s — sound, color, widescreen bringing developing language — then beginning, finally, to open up in the current century to voices previously suppressed and denied, Cinema, so Linklater suggests, nevertheless may be withering on the vine.

Why does he say this? Is it true? Coming from such a brilliant cineaste, the comment surely warrants our singular attention.

Established and revered exponents are still going strong. From Scorsese to Wenders to Spielberg to Herzog, from Campion to Almodóvar, from Kaurismaki to Holland the work keeps coming, often among the best of their respective oeuvres. (Haneke, sadly, has been missing in action for a while now, while Terence Davies has been lost to us too soon.)

More recent generations continue to bring astonishing work to the screen.There hasn’t been a movie from Lynne Ramsay for a while but Andrea Arnold’s cinematic Cow from a couple of years ago is a gem. Bong Joon Ho persists in amazing us. Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla constitutes yet another fine film from this intensely intelligent, deeply engaging director. Nolan is at his best with Oppenheimer, Haynes with May December, Payne with The Holdovers.

Of late, we have Yorgos Lanthimos, Barry Jenkins, Ari Aster, Chloe Zhao, Celine Sciamma, Sam Esmail, Julie Ducournau, Alice Diop, Kauther Ben Hania, Charlotte Wells, and so many others.

You may disagree with specific examples here and there (and of course those cited go nowhere near to scratching the surface), but the nature of the generational flow of substantial cinematic outpouring seems to me undeniable.

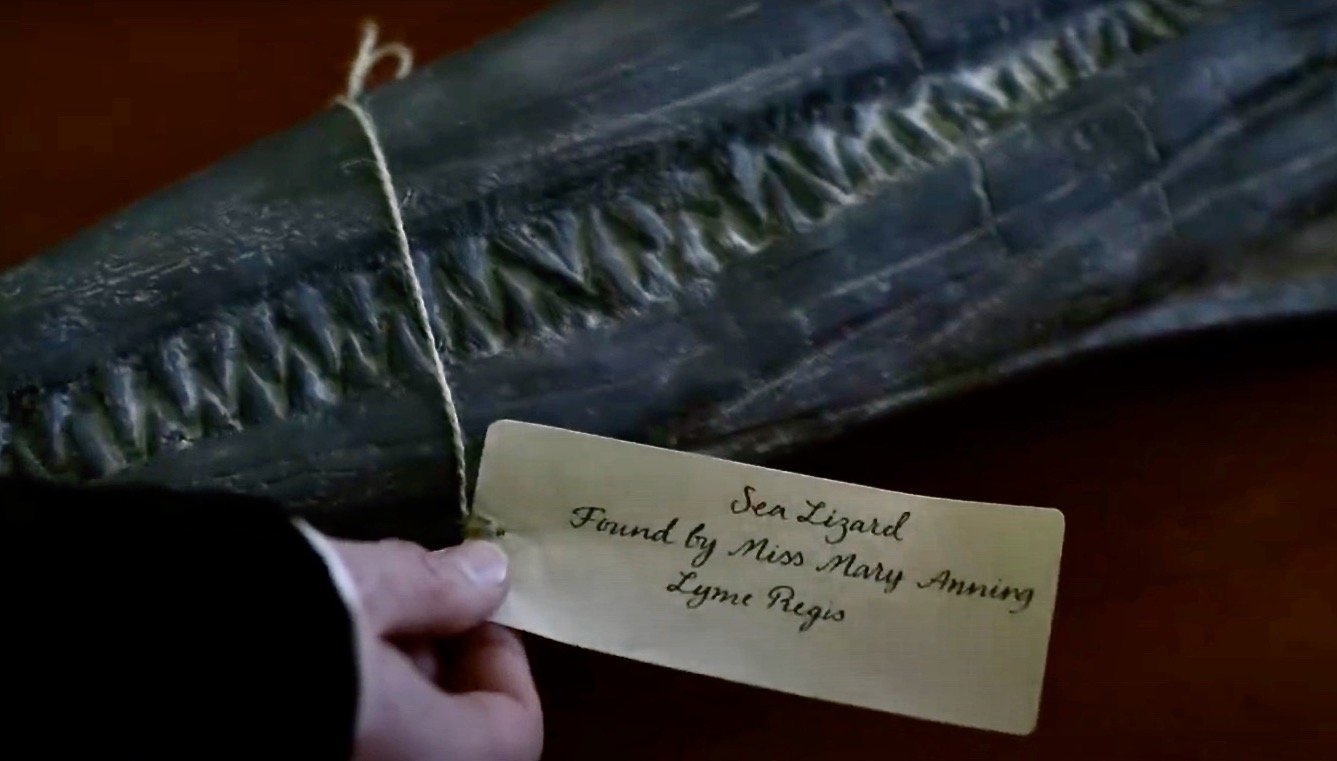

In just the last couple of years the output has been overwhelming. We have Celine Song with Past Lives, every element of cinematic language articulated on the screen. There’s Hlynur Pálmason’s Godland, its cinematography by Maria von Hausswolff limpid, breathtaking as the landscapes it presents, crystal precise as the portraits it paints.

The sheer number of remarkable movies and movie-makers continues to be astonishing.

Should we be considering other factors though?

The development of streaming as an element in the Linklater pessimism perhaps? The filmmaking giants now work with Netflix, Apple, Amazon however. This way, they’ve been able to give us movies the studios would never have greenlit. (As a half-American do I say ‘greenlighted’?) But is this a mixed blessing?

Watching on TV, on this device or that, does this keep viewers from the big screen? Many movies wouldn’t get made unless they are streamed though; there wouldn’t be audiences for them in the theatres because they wouldn’t exist in the first place.

How about the preponderance of tablets, iPads, smartphones, etc. Is this causing the language of visual storytelling to change? And for the worse?

But is this change such a bad thing? Doesn’t a language need to keep evolving if it’s to stay alive? Mightn’t those devices inform that evolution? Is screen language really becoming less ‘cinematic’ as a consequence of their use or is it becoming more flexible, growing in its forms of address by drawing on our various current modes of visual interlocution?

When TV made its entry into the lexicon of the screen, there were at least a couple of ways in which Cinema responded. Close-ups became more prominent, for example. The wide screen was adopted more and more. (Here close-ups became less prominent when some directors simply treated the frame as though it were depicting a stage, its lateral axis containing the action in wide shot.) The Cinerama format of 2.65:1 (three 35 mm cameras covering the action, three projectors and a curved screen its machinery) was seen as a way of attracting audiences away from their Academy Ratio (4:3) TV sets. 1.85:1, 2.35:1 were also tempting while at a time of black and white TV, Technicolor in the movie theatre was also considered a draw.

Now though, new filmmakers are reverting — if reverting is the right word — to academy ratio. The power of the vertical, as opposed to the lateral axis, is again being recognized. (See the above frame from Godland.) Perhaps not so much in mainstream, commercial movies though…

And as for black and white — what Wim Wenders once described as ‘the most beautiful colors’ — the palette was not long excluded from movie discourse .

Are these concerns — of the nature the screen we watch a movie on, its technology, its shape — irrelevant to the question of cinema’s survival however?

Is there a more of a problem in the movies that are made, distributed, and consumed? Movies of particular types? Franchise movies? Superhero movies? And the nature of the industrial structure that enables their manufacture?

Is it also a question of audiences and their acculturation? Their expectations? Their concept of the film viewing experience? Does it follow that, because of types of movies currently prevalent and a movie theatre environment geared to seducing the viewer into becoming a pampered consumer of them, audiences are becoming less discriminating? Is it that Cinema needs discerning adherents in order to survive?

Writing in 1926, Virginia Woolf commented: People say that the savage no longer exists in us, that we are at the fag-end of civilization, that everything has been said already, and that it is too late to be ambitious,”. But these philosophers have presumably forgotten the movies…

And she continued, in relation to the act of watching a film: The eye licks it all up instantaneously, and the brain, agreeably titillated, settles down to watch things happening without bestirring itself to think.

Later, she gives the game away when she says: Is there, we ask, some secret language which we feel and see, but never speak, and, if so, could this be made visible to the eye? Is there any characteristic which thought possesses that can be rendered visible without the help of words?

What was she talking about? Of course thought processes can be rendered visible without words. Simply cutting from a look to what the looker sees then cutting back to their reaction, for instance, reveals a character’s thoughts. The actor’s nuances of expression reveal a character’s thoughts. A camera move, its placement, a cut, color, lighting, soundscape, score, composition, mise-en-scène may all convey thought processes.

She complains that movies dumb down audiences only to then reveal she has no idea of how the language of the screen works. (Nor could most viewers articulate this, although they nevertheless understand it.) Presumably, given the date of these observations, she’s talking about silent movies. She’s writing in the year before Gance’s Napoleon is released and a quarter of a century into filmmaking by Chaplin and Griffiths, in the age of Eisenstein, Von Stroheim, early Lang, early Dreyer.

Such filmmakers already brought a rich, highly developed film language. Audiences were smart enough to follow it then — as they are today.

So does it come down to the stories we are being fed these days? Simplistic combat between good and evil, Manichaean struggles to be won by the superheroes who once were the gods that all Americans, no matter ethnicity or faith, could worship, but who have now become the interchangeable cyphers generated by corporate business. Has product replaced myth, the eyes taking in the pabulum on the screen as the stomach absorbs the junk concessions accompanying it?

Maybe, maybe, maybe… but let’s not forget those amazing new filmmakers, and where they come from, and what they bring that is new and fresh.

Even as a straight white male, as a working class London boy I was told that I would never get into filmmaking in any capacity whatsoever because ‘you don’t know the right people.’ (The English class system — don’t you just love it.)

Think (or perhaps you know) how much more of an impossible mountain to climb this aspiration has been for a woman, or anyone from most of the world’s population, who don’t look like me. Movie-making, for most of its history, it goes without saying, has been the province of the well-to-do male. (Scorsese is one of the few giants to emerge from the working class.) Now the barriers are coming down, even if there remains a way to go.

It is from these previously ignored, disenfranchised swathes of humanity that the survival–NO, THE REAWAKENING — of Cinema is coming about.

A Cinema for all of us. The screen of the human soul. What’s in you, what’s in me, up there in the language of the image: moving, static, beguiling, shocking, tempting, repelling, mesmerizing, sobering, oneiric, inflected, uninflected, devastating, revelatory, transgressive, decorous, indecorous, magical, austere, flamboyant, intricate, plain, serene, dynamic, subversive, celebratory, unflinching, reaching out and reaching in — to our perception, our thought, our visceral sensation, our emotion, to the very nature of our being…

Like us, as Cinema — as it lives and breathes, the equal of any art — ever affirms.

Peter Markham January 2024