Sometimes I wish it would stay. Sometimes I wish it would go away. (Paul McCartney: McCartney III)

Sakuro Ando as Nobuyo Shibata in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters. (Cinematography by Kondo Ryuto.)

On the screen, in the hearts of the audience, in the course of a story, at its denouement, emotion is Cinema’s most precious gift. In tandem with existential vision (Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland), orchestrated by trenchant intellect (Michael Haneke’s Amour), unleashed through the stealth of patient narrative (Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire), conveyed achingly in each and every frame (Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu), emotion is both the punishment and the reward we take from the films that count.

Why do I say punishment? Because emotion can hurt. It can hold us in its ruthless grip. Can render us desperate for release. Can keep us awake during the night long after a film has finished. Can return to us unannounced. Why do I say reward? Because the word suggests a recompense for a task carried out, for work that’s been completed, a pleasurable bounty but also perhaps one more problematic—the just desserts maybe, for our complicity in a journey of dubious moral complexion (Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here). Emotion is the deepest experience of the characters we watch, and of ourselves as we watch them. They may perceive, they may think, they may know, they may act, but it’s when they feel that the screen delivers its coup de cinema, us at its receiving end.

And when a character suppresses or hides an emotion too painful for them to bear, when they hold back a tear so that it is we who shed it for them, that blow is intensified. When, as Krzysztof Kieślowski commented, a director also partly conceals emotional pain, perhaps shooting a character from behind or in conjunction with the cinematographer, cloaking them in shadow, the resonance somehow hits harder—not Show, don’t tell! but Obscure, don’t show! There will be times too, when a character is unaware of the danger they are in, or they fail to make a connection we have made so we fear for them, or we anticipate their joy on the discovery we understand they are themself soon to make. Here the emotion arises from situation and storytelling, the interplay of world within the film and world within the audience.

Always make the audience suffer as much as possible, Alfred Hitchcock, my fellow Londoner—true to the city’s perennially roguish spirit—observed. And this he did, yet audiences loved his movies, still do, many of them—while even some of those falling short upon their release proved later to be masterpieces. Hitchcock knew that the more he made an audience suffer, the more grateful it would grow. The Safdie Brothers could have been bearing this in mind as they made Uncut Gems—look at how many of us thrill to that film. He knew that we come to a movie as we come to a novel or a short story, in order to suffer. But why? Usually we go out of our way to avoid pain. Why then should we spend time and money to experience it?

Author Anaïs Nin wrote …nothing that we do not discover emotionally will have the power to alter our vision.

When locked into a mindset, maybe bounded by a story, a myth, a culture, and the sense of identity and belonging they foster, or when we have succumbed to common thinking and someone comes along to argue the contrary, we are unlikely to shift our position. We tend to strengthen our views in fact. Driven to defend ourselves, we grow even more convinced of our perspective.

How different that outcome is from when we follow the journey of a protagonist in a novel or film—eventually, at least in the best of cases, finding the character has some moment of realization we come to share. We adhere to a voyage of rage for example, a path to righteous justice, only to discover our protagonist becoming much the same manner of violator as the perpetrator they and we wish to see punished. (The Limey.) Or after the protagonist has become deaf and like him we long to find a cure, we both learn that it is silence that perhaps offers the most profound sense of being alive. (The Sound of Metal.) Reading those sentences, we might understand their point intellectually, but watching those films and following their narratives, we grasp their truths through the voyage of emotion, especially that we feel as the movies arrive at their end.

Is this what Aristotle, polymath among the ancients, was describing, when he talked of catharsis? Usually this concept is thought of as the “purging” of emotions, as though emotions were—in and of themselves—toxic. Emotions can throw us off balance, yes. They can lead us to act unwisely and commit actions we later come to regret. They can make us feel ill, deliriously happy, desperately needy, confused, compassionate, hostile—the litany never ends. One way or another, they can disturb some supposed equilibrium. Is that the complete picture though?

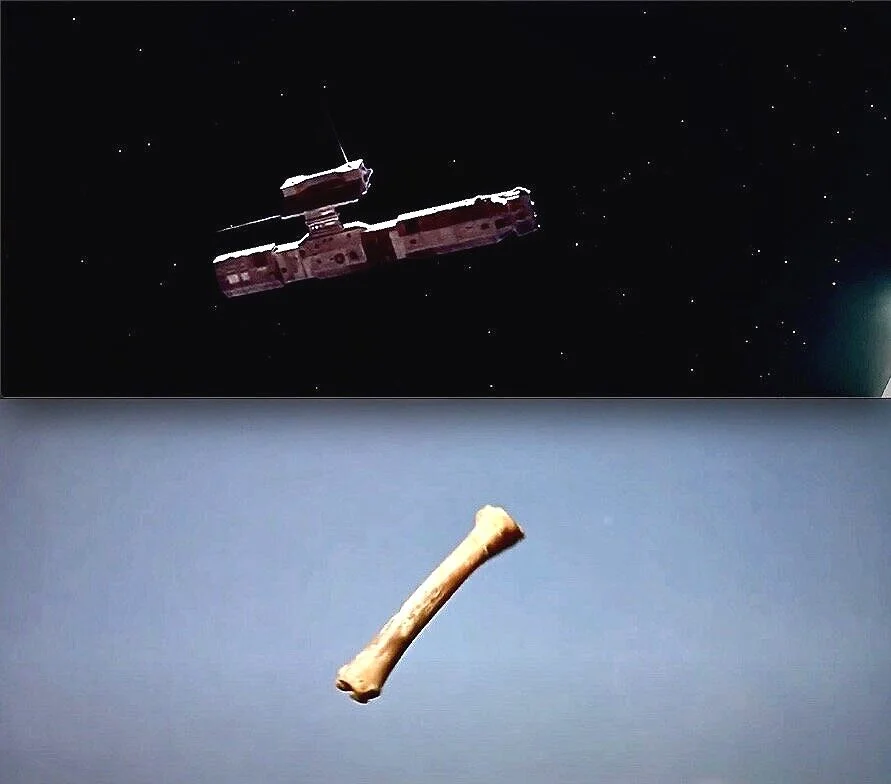

I like to keep in mind another meaning of the word katharsis contemporary to Aristotle—namely understanding. Bear with me, because I don’t believe that emotions need to be swept away at all. It seems to me that true revelation comes with and through emotion. Indeed, it cannot come without it. At the end of Chung Mong-hong’s A Sun, for example, I feel intense emotion, and this remains with me in the wake of the movie—in the ensuing minutes, in the night after, the next day, and even during the following weeks. The emotions the characters have experienced have been deeply unsettling. Those the viewer has endured, have been similarly rough—the instances of dark comedy complicating and contradicting this relationship—even if our actual emotions are of course generally less traumatic than the characters’ fictional feelings. (These latter exist only in a world of make-believe, remember, although they may have been conjured by the actors on the set—take a look, for example, at Sakuro Ando in her scene towards the end of Shoplifters, when her flow of emotion possesses the frame—or they may not, story and storytelling alone the originators.) Have our feelings been expelled when A Sun is over? The main characters are in a better place while I am deeply moved—to tears, if I’m honest. So what has been purged?

This final rush of emotion follows from realization, what I believe Aristotle called the anagnorisis, on a character’s part and on our own. Surely this represents an acceptance of all we have felt, which we can now see through a fresh perspective—the understanding that only a journey of emotion can bring. Emotion regarded in this way is not merely a bio-chemical drug, an imbalance of the metabolism, even a disturbance, but a form of profound intelligence, a cognition, a resonance that continues once the plot, and the story it supported, is over.

There are films throughout which we can remain very profoundly engaged emotionally, that deliver this final gift, perhaps in accord with their journey thus far, perhaps through some unexpected twist. There are films that render us listless, even bored, but then take us by surprise, leaving us shaking with feeling as the credits roll, as if we’ve been ambushed by the filmmakers. There are films that by contrast peek our emotions throughout, often through the layering of conflict, through performance, lighting, cutting, and score, but at their end fall short—consumerist confections of feeling that calculate themselves into emptiness. How robbed we feel at the end of those latter follies! How empty! It’s the sense of fulness, the fulness of our human selves, our souls, that true Cinema gives, the transmuting of our emotions from burdens and manipulators into the entities that make us what in total we are, which draws us to film.

This is the reward, the awareness of ourselves, for better or worse, that we seek. It can awaken us. It can trouble us. It can surprise. It can affirm. Whichever, it leaves us feeling alive—and accepting of our being in the world, for all the fathomless uncertainty of our predicament.

New filmmakers take note! Take care not to protect your audience—or yourselves—from the emotions inherent in your story. Embrace the pain! Drown in the joy! Feel it! Write it! Shoot it! Put it up on the screen, whether obliquely or directly but make sure it’s there. We need it…

It’s the essence.

Peter Markham March 2021

Author: What’s the Story? The Director Meets Their Screenplay. (Focal Press/Routledge)

https://linktr.ee/filmdirectingclass