(Citizen Kane, Director: Orson Welles, Screenplay: Herman J. Mankiewicz, Welles, Cinematography: Gregg Toland / Vertigo, Director: Alfred Hitchcock, Screenplay Alec Coppel, Samuel Taylor, Cinematography Robert Burks.)

A friend recently introduced me to a book that claims profound insights into how artists set about their work. Old Masters and Young Geniuses by David W. Galenson https://bookshop.org/books/old-masters-and-young-geniuses-the-two-life-cycles-of-artistic-creativity/9780691133805 posits the notion that there are polarities of creative process, the conceptual and the experimental.

The conceptual approach, Galenson writes, is the M.O. of the artist, writer, director who first gets an idea, plans their work meticulously, then once ready, paints, writes, or shoots and cuts it to its pre-planned perfection. No hesitation, no stumbling, little sweat—100 per cent inspiration, zero per cent perspiration. That achieved, maybe a few times over, they move on to a new concept, nail that, then again move on to a fresh domain. Galenson gives Picasso as an example, his work marked by distinct conceptual shifts that each changed the nature of his canvases, changing perceptions of painting itself. Others follow in the wake of such a figure, adopting their assumptions, techniques, aesthetic tenets, and manifestos.

Conceptualists tend to do their best work early in their careers. Later efforts tend to be less sought after, less significant. Their reputations are as early bloomers.

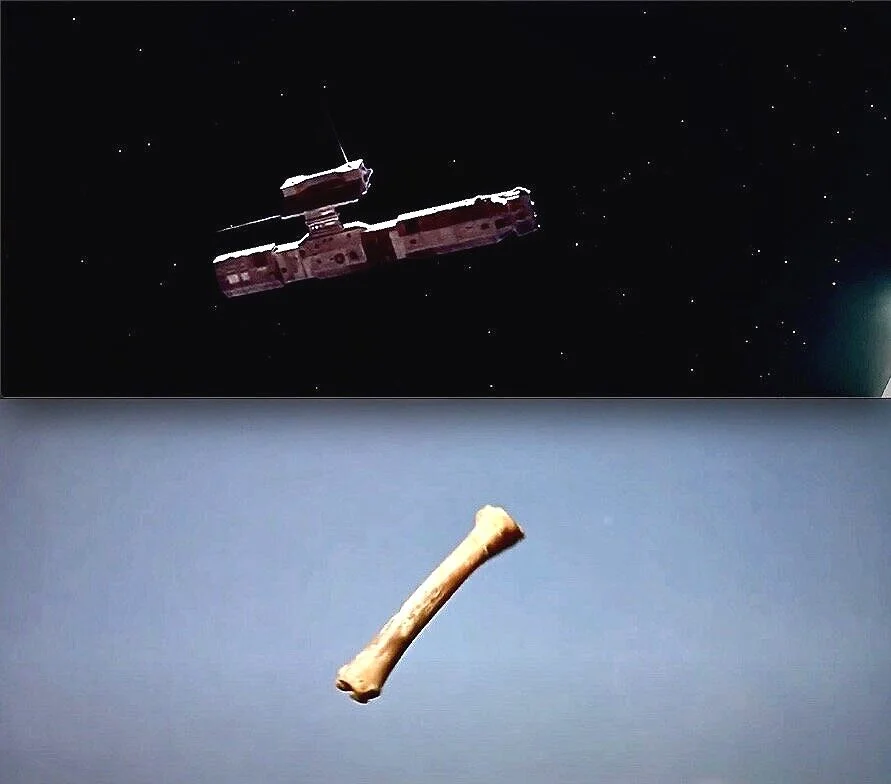

A filmmaker he cites in this respect is Orson Welles, whose Citizen Kane follows the life of a driven, less than attractive protagonist through the wide lenses, deep focus, and low angles of Gregg Toland’s famed cinematography. Like Picasso, Welles’ produced his most highly regarded work, Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons in his case, in his twenties. The terms ‘boy wonder’ and ‘enfant terrible’ come to mind. (Qualification: Touch of Evil came later.)

The conceptualists are the finders.

The experimental approach is the M.O. of the artist, writer, director who looks for their idea through the process and agony of creating the work itself, who lack any template to be faithfully followed. A term used at the film school in which I taught was NATO—not attached to outcome, which I always thought supportive of the dedicated student striving to create successful work but unsure of its precise eventual nature. Such an artist will have a limited sense of exactly where their work is going but will beaver away through successive versions, drafts, cuts until they have something they must finally step away from. Galenson gives the example of painter Paul Cezanne, who admitted he was never sure how any of his paintings would finish up.

In contrast to the conceptualists, the experimentalists tend to create their best work later in their careers. They are the late bloomers. It’s their ‘work ethic’ that yields their achievement. (What in the world has work to do with ethics? Work describes activity, not morality.)

A good traveler has no fixed plans, and is not intent on arriving, said Lao Tzu. The experimentalist is perhaps such a traveler, with no fixed plans—with little idea even of their eventual destination.

A filmmaker Galenson posits in this respect is Alfred Hitchcock, whose greatest films, unlike those of Welles, are generally considered to be those of his later career (if not the ones of his final years). Hitchcock’s preoccupations can be traced throughout his canon of course—transference of guilt, son-mother relationships, icy blondes, oneiric ventures into the psyche, heights and acrophobia as sublimated dread of sexual impotence—but somehow in Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, Marnie they appear most organically encapsulated into story, character, and visual language than in his earlier films, impressive as many may be.

This is Hitchcock as ‘old master’, the opposite to Welles as ‘young genius’.

The experimentalists are the searchers.

Here I find myself wondering what a clear, obvious example from human history of the conceptual approach in terms of creativity and inventiveness might be. Perhaps the wheel. The wheel has to have been invented in one fell swoop. You wouldn’t come up with a single segment, see it not work, add a second segment, witness the failure of that, add a third and a fourth and so on until you ended up with the first ever complete wheel, one that finally worked. No. The wheel had to have come about in one conceptual leap (or revolution more like).

What, I ponder, might have proved a contrasting example of experimentalism? Think about Italian writer Italo Calvino’s insight into the folk tale—Calvino said that anonymously written folk tales took shape over generations. They achieved their perfection through the collective, generational mind of storytellers over the centuries, each adding, subtracting, shifted, re-working the drafts of their predecessors. Were it not for the tales being committed to the page and so finally, as it were, frozen in time, maybe the process would be continuing, never to stop perhaps, each generation imbuing such narratives with its own take.

But is Galenson being overly schematic? Is his reductivist, statistics-based approach adequate in revealing the process of the artist? Doesn’t the creative act require both a degree of conceptualism and a measure of experimentalism? Doesn’t the conceptualist undergo more than a few drops of perspiration as they set out their templates? And don’t they sweat the odd bead in finally executing their work? Doesn’t the experimentalist require the odd moment of inspiration, those instances when some insight strikes, when an answer mysteriously reveals itself as the artist is making a coffee, taking a shower, out for a walk after hours upon hours at their desk when the solution eluded them?

When the solution came, it came, as always, through the back door of the mind, hesitating shyly, an announcing angel dazed by the immensity of its journey, wrote John Banville in his novel Kepler. Is that how these pearls of progress arrive, delivered by some dazed ‘angel’ from some distant, unfathomable place, the domain of wisdom whose messages to most of us are intermittent at best?

Galenson believes that a conceptualist can become an experimentalist, but an experimentalist can never become a conceptualist. The former may at some point forego their blueprints and move straight to the canvas—the literal one or its metaphorical counterpart—there to make the adjustments necessary to finalize the work, in the process discovering changes that blueprints could never have prompted. The experimentalists on the other hand need the ordeal of constant revision, the re-writing—which is where the actual writing happens. They will never change into a conceptualist because they cannot overcome their hard-wiring. This doesn’t matter, Galenson argues, because art is achievable through either approach.

While I agree that the polarities can indeed be found in particular young geniuses and old masters, and that one movement, Impressionism say, or Abstract Expressionism, may have been driven by experimentalism while the schools that followed were founded on the opposite, for most artists—and I would argue, filmmakers included—there exists more a shifting spectrum. Hitchcock, for example, in contrast to Galenson’s evaluation, did show the traits of a conceptualist throughout his career. He was especially prepared before setting foot on the set, leaving little to chance: Many people think a film director does all his work in the studio, drilling the actors, making them do what he wants. That is not at all true of my own methods… And indeed, it wasn’t. For Hitchcock, “prep” was as much process as the shoot and the cut, even more so.

As an experimentalist on the other hand, he also developed as a filmmaker, honing the exploration and articulation of his obsessions over the course of his career. From The Lodger (1926) through films such as Notorious (1946) to Psycho (1960), and on to Marnie (1964), his movies bring the power of the mother figure to the screen with ever increasing potency, not to mention psychic disturbance.

So… what are you yourself? Conceptualist or experimentalist? Or are we all, should fortune smile on us, to greater or lesser extent something of both?

Peter Markham May 2021

Author: What’s the Story? The Director Meets Their Screenplay. (Focal Press/Routledge)

https://linktr.ee/filmdirectingclass